Measuring the scale of research and innovation helps estimate how well research or innovation efforts are performing. In simple terms, research performance is about how effectively a project or study reaches its goals. When research achieves its objectives, it often leads to new findings, better methods, or even practical applications of that research. To measure this performance, we look at different factors that show the results of the research. These factors can include things like the number of published papers, the citations they attract, patents filed, social benefits created, or even the production of innovative, disruptive ideas.

Traditionally, the most popular way to track the scale of science has been to count new journals and, later, the number of articles published. The field of scientometrics—which studies how to measure science—began by focusing on how science grows. Pioneers like Alfred Lotka, Samuel Bradford, George Zipf, and Derek de Solla Price laid the groundwork for this field. Today, science can also be measured by looking at grants awarded or non-traditional outputs like blog posts, performances, or designs.

One common way to measure scale is by counting the number of results, such as how many research papers are published. This is often considered as a measure of productivity. However, simply counting papers or patents is not always the best way to measure true productivity. Since articles, patents, and other written outputs are key to research, the concepts they contain can help us understand research and innovation. Using papers and patents as indicators of scientific and technical progress is based on solid theory, even though this approach has some limitations. This method is also widely used in the study of research and innovation, forming the foundation of scientometrics as a research discipline.

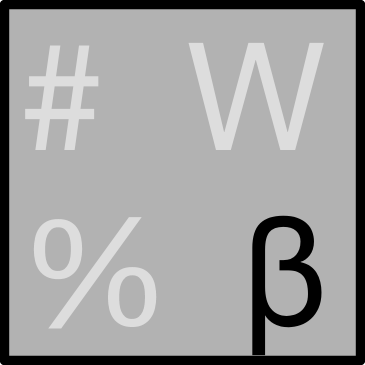

Overall, the scale of research and innovation can be measured by counting the outputs or results of activities. This includes the number of papers published, patents filed, projects completed, and other types of results. Four mesurements can be derived from these counts:

#, The total count (for example, France produced 100 papers in 2024).

W, The weighted count (for instance, France produced 110 weighted papers when each paper is weighted by their relative citation index of 1.1). Weighted counts need to be used with care.

%, The share expressed as percentage or a frequency of the total count (for example, France produced 20% of EU papers).

β, The relative index such as the Revealed comparative advantage (RCA) which an index expressing the degree of specialisation or investment (for example, with a RCA of 1.2 (>1) in ecology, France is more specialised than the rest of the EU).1

- Also known as the Balassa-index, from: Trade liberalisation and revealed comparative advantage, Balassa, B., Manchester School of Economic and Social Studies, 1965, Volume 33, Issue 2, Pages 99-123, DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9957.1965.tb00050.x ↩︎